Numbers can be so much more than numbers. Measurements of speed, distance and weight may embody levels of idiomatic and cultural meaning.

Going the distance

We might discuss the fuel usage of our cars, and in the UK although fuel is sold and priced by the litre, many of us still think of cars as going a certain number of miles (since that’s what the road signs say) per gallon.

When buying and selling cars, we often ask each other how far the car has already been driven. So we ask each other whether that’s a high mileage car, or what mileage you get from your car? We answer with things like a number of ‘quite high’ or ‘pretty low, considering its age (or performance, etc.)’. Mileage collocates with ‘calculator’, a device to work out how many miles (displayable of course in kilometres) a journey will take when you look online. It also collocates with ‘check’ (sensible to have that done when buying a used car) and ‘allowance’ and ‘rates’ (which you need to know for expenses claim forms and tax returns).

Travelling further

Well, I’ve never heard of kilometerage. So then how will a translation follow the thread into other areas? Some are quite close, for example, ‘I got a lot of mileage out of my dishwasher before it finally broke down.’

Others start to move away a little: ‘Michael always got a lot of mileage out of that one joke.’ And into quite dull business settings too: ‘Clara is trying to get as much mileage as she can out that tired old idea.’ ‘I don’t think we’ll get much mileage out of the latest proposal – it’s not going to convince many people.’

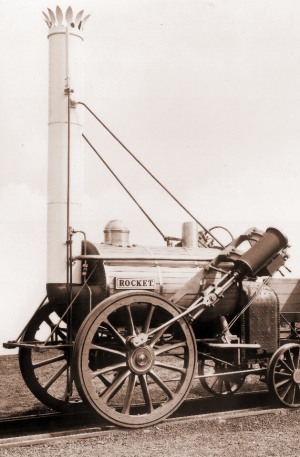

Actually, you could express some of these with older forms of transport. We’ll know what you mean if you say that your dishwasher has finally ‘run out of steam’, even though steam-powered transport is a thing of the past.

Actually, you could express some of these with older forms of transport. We’ll know what you mean if you say that your dishwasher has finally ‘run out of steam’, even though steam-powered transport is a thing of the past.

Old models

And you can follow that line of technological detritus littering the language with its archaisms that so stubbornly persist, when they are surely past their sell-by dates. Why do we talk about ‘hanging up’ the phone (which hasn’t physically happened in my lifetime, except in black-and-white films), ‘dialling a number’ (and not pressing numbers) or ‘ringing’ (for no-one tolls a bell anymore)?

As easy as 1, 2, 3?

What about if you stick with really simple things, like basic numbers, and learning to distinguish similar-sounding numbers? This is a very important basic thing, and means you’ll pay the right money, catch the right train from the right platform, and so on.

In English, you need to distinguish ‘thirteen’ and ‘thirty’ (as much a question of stress as phonemes) and to keep an eye or ear on ‘three’. Does this work the same in French? There you have, respectively, ‘treize’, ‘trente’ and ‘trois’. Are they more or less confusable than the Spanish ‘trece’, ‘treinta’ or ‘tres’? What about Turkish: ‘on iki’, ‘otuz’ and ‘üç’? Maybe that nugget of confusable 3s is a Latin thing…

Called to account

We have to accommodate changes in numbering systems, including currencies (of the financial kind). If I have some nice English tests and there’s a tidy little listening task with two people discussing the price of something, then the discussion might involve whether you get three for £30 or whether they’re £13 each and so on. Worth testing, because it’s genuinely meaningful.

But if the UK joins the Euro (just to wipe the smug smile off Nigel Farage’s face), then how will we translate that discussion and its questions? At today’s rates, I can’t see many candidates being sorely tested when distinguishing between three for €37 (or even €36.87) or whether they’re €16 (or even €15.98) each.